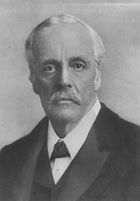

Arthur Balfour

| The Right Honourable The Earl of Balfour KG OM PC DL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 11 July 1902 – 5 December 1905 |

|

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Preceded by | The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

|

Leader of the Opposition

|

|

| In office February 1906 – 13 November 1911 |

|

| Monarch | Edward VII George V |

| Prime Minister | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman Herbert Henry Asquith |

| Preceded by | Joseph Chamberlain |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Bonar Law |

| In office 5 December 1905 – February 1906 |

|

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Prime Minister | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| Preceded by | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Chamberlain |

|

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

|

|

| In office 10 December 1916 – 23 October 1919 |

|

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | Sir Edward Grey |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Curzon of Kedleston |

|

First Lord of the Admiralty

|

|

| In office 25 May 1915 – 10 December 1916 |

|

| Prime Minister | Herbert Henry Asquith David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | Winston Churchill |

| Succeeded by | Sir Edward Carson |

|

Lord President of the Council

|

|

| In office 27 April 1925 – 4 June 1929 |

|

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | The Marquess Curzon of Kedleston |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Parmoor |

| In office 23 October 1919 – 19 October 1922 |

|

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | The Earl Curzon of Kedleston |

| Succeeded by | The 4th Marquess of Salisbury |

|

Lord Privy Seal

|

|

| In office 11 July 1902 – September/October 1903 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury |

| Succeeded by | The 4th Marquess of Salisbury |

|

Member of Parliament

for Hertford |

|

| In office 1874–1885 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert Dimsdale |

| Succeeded by | Abel Smith |

|

Member of Parliament

for Manchester East |

|

| In office 1885–1906 |

|

| Preceded by | New Constituency |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Gardner Horridge |

|

Member of Parliament

for City of London |

|

| In office 1906–1922 |

|

| Preceded by | Alban Gibbs |

| Succeeded by | Edward Grenfell |

|

|

|

| Born | 25 July 1848 Whittingehame, East Lothian, United Kingdom |

| Died | 19 March 1930 (aged 81) Woking, Surrey, United Kingdom |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse(s) | none |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge, United Kingdom |

| Profession | Member of Parliament |

| Religion | Church of Scotland and Anglican |

| Signature | |

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, KG, OM, PC, DL (25 July 1848 – 19 March 1930) was a British Conservative politician and statesman. He authored the Perpetual Crimes Act (1887) (or Coercion Act) aimed at the prevention of boycotting, intimidation, unlawful assembly in Ireland during the Irish Land War, and was the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905, a time when his party and government became divided over the issue of tariff reform. Later, as Foreign Secretary, he authored the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which supported the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Contents |

Background and early career

Arthur Balfour was born at Whittingehame, East Lothian, Scotland, and was the eldest son of James Maitland Balfour (1820–1856) and Lady Blanche Gascoyne-Cecil (d. 1872, aged forty-seven). His father was a Scottish MP; his mother, a member of the Cecil family descended from Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, was the daughter of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury and a sister to the 3rd Marquess, the future Prime Minister. His godfather was the Duke of Wellington, after whom he was named.[1] He was the eldest son, the third of eight children, and had four brothers and three sisters. Arthur Balfour was educated at the Grange preparatory school in Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire (1859–1861), Eton (1861–1866) where he studied with the influential Master William Johnson Cory, and Trinity College, Cambridge (1866–1869),[2] where he read Moral sciences, graduating with a Second-Class Honours Degree. His younger brother was the renowned Cambridge embryologist Francis Maitland Balfour (1851–1882).

Although he coined the saying, "Nothing matters very much and few things matter at all," Balfour was distraught at the early death from typhus in 1875 of his cousin May Lyttelton, whom he had hoped to marry. Balfour remained a bachelor for the rest of his life, his serious intention to marry never renewed. Margot Tennant (later Margot Asquith) had wished to marry him - on being queried about this he replied "No, that is not so. I rather think of having a career of my own." [1] His household was maintained by his (also) unmarried sister Alice. In middle age Balfour had a long friendship with Mary Wemyss, later Countess of Elcho. It is unclear whether the relationship was sexual.

In 1874 he was elected Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Hertford and represented that constituency until 1885. In the spring of 1878 Balfour became Private Secretary to his uncle, Lord Salisbury. In that capacity he accompanied Salisbury (then Foreign Secretary) to the Congress of Berlin and gained his first experience in international politics in connection with the settlement of the Russo-Turkish conflict. At the same time he became known in the world of letters; the academic subtlety and literary achievement of his Defence of Philosophic Doubt (1879) suggested that he might make a reputation for himself as a philosopher.

Balfour divided his time between the political arena and the academy. Released from his duties as private secretary by the general election of 1880, he began to take a more active part in parliamentary affairs. He was for a time politically associated with Lord Randolph Churchill, Sir Henry Drummond Wolff and John Gorst. This quartet became known as the "Fourth Party" and gained notoriety for the leader Lord Randolph Churchill's free criticism of Sir Stafford Northcote, Lord Cross and other prominent members of the "old gang".

Service in Lord Salisbury's governments

Lord Salisbury made Balfour President of the Local Government Board in 1885 and later Secretary for Scotland in 1886, with a seat in the cabinet. These offices, while having few opportunities for distinction, served as a sort of apprenticeship for Balfour. In early 1887 Sir Michael Hicks-Beach, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, resigned because of illness and Salisbury appointed his nephew in his place. The selection took the political world by surprise and possibly led to the British phrase "Bob's your uncle!". Balfour surprised his critics by his ruthless enforcement of the Crimes Act, earning the nickname "Bloody Balfour". Balfour's skill for steady administration did much to dispel his reputation as a political lightweight.

In Parliament he resisted any overtures to the Irish Parliamentary Party on Home Rule, and, allied with Joseph Chamberlain's Liberal Unionists, strongly encouraged Unionist activism in Ireland. Balfour also broadened the basis of material prosperity to the less well off by creating the Congested Districts Board for Ireland in 1890. It was during this period of 1886-1892 that he sharpened his gift of oratory and gained a reputation as one of the most effective public speakers of the age. Impressive in matter rather than in delivery, his speeches were logical and convincing, and delighted an ever wider audience.

On the death of W.H. Smith in 1891, Balfour became First Lord of the Treasury - the last one in British history not to have been concurrently Prime Minister as well — and Leader of the House of Commons. After the fall of the government in 1892 he spent three years in opposition. On the return of the Conservatives to power in 1895, he resumed the leadership of the House. His management of the abortive education proposals of 1896 were thought to show a disinclination for the continuous drudgery of parliamentary management. Yet he had the satisfaction of seeing a bill pass providing Ireland with an improved system of local government, and took an active role in the debates on the various foreign and domestic questions that came before parliament between 1895 to 1900.

During the illness of Lord Salisbury in 1898, and again in Lord Salisbury's absence abroad, Balfour was put in charge of the Foreign Office, and it was his job to conduct the critical negotiations with Russia on the question of railways in North China. As a member of the cabinet responsible for the Transvaal negotiations in 1899, he bore his full share of controversy, and when the war began disastrously, he was the first to realise the need to put the full military strength of the country into the field. His leadership of the House of Commons was marked by considerable firmness in the suppression of obstruction, yet there was a slight revival of the criticisms of 1896.

Prime minister

On Lord Salisbury's resignation on 11 July 1902, Balfour succeeded him as Prime Minister, with the approval of all sections of the Unionist party. The new Prime Minister came into power practically at the same moment as the coronation of Edward VII and the end of the South African War. For a while no cloud appeared on the horizon. The Liberal party was still disorganised over their attitude towards the Boers. The two chief items of the ministerial parliamentary program were the extension of the new Education Act to London and the Irish Land Purchase Act, by which the British exchequer would advance the capital for enabling tenants in Ireland to buy land. A notable achievement of Balfour's government was the establishment of the Committee on Imperial Defence.

In foreign affairs, Balfour and his foreign secretary, Lord Lansdowne presided over a dramatic improvement in relations with France, culminating in the Entente Cordiale of 1904. The period also saw the acute crisis of the Russo-Japanese War, when Britain, an ally of the Japanese, came close to war with Russia as a result of the Dogger Bank incident. On the whole, Balfour left the conduct of foreign policy to Lansdowne, being largely busy himself with domestic problems.

The budget was certain to show a surplus and taxation could be remitted. Yet as events proved, it was the budget that would sow dissension, override all other legislative concerns, and in the end signal the beginning of a new political movement. Charles Thomson Ritchie's remission of the shilling import-duty on corn led to Joseph Chamberlain's crusade in favour of tariff reform — these were taxes on imported goods with trade preference given to the Empire, with the threefold goal of protecting British industry from competition, strengthening the British Empire in the face of growing German and American economic power, and providing a source of revenue, other than raising taxes, for the costs of social welfare legislation. As the session proceeded, the rift grew in the Unionist ranks. Tariff Reform proved popular with Unionist supporters, but the threat of higher prices for food imports made the policy an electoral albatross. Hoping to split the difference between the free traders and tariff reformers in his cabinet and party, Balfour came out in favour of retaliatory tariffs—tariffs designed to punish other powers that had tariffs against British goods, supposedly in the hope of encouraging global free trade.

This was not, however, sufficient for either the free traders or the more extreme tariff reformers in the government. With Balfour's agreement, Chamberlain resigned from the Cabinet in late 1903 to stump the country in favour of Tariff Reform. At the same time, Balfour tried to balance the two factions by accepting the resignation of three free-trading ministers, including Chancellor Ritchie, but the almost simultaneous resignation of the free-trader Duke of Devonshire (who as Lord Hartington had been the Liberal Unionist leader of the 1880s) left Balfour's Cabinet looking weak. By 1905 relatively few Unionist MPs were still free traders (the young Winston Churchill crossed over to the Liberals in 1904 when threatened with deselection at Oldham), but Balfour's long balancing act had drained his authority within the government.

Balfour eventually resigned as Prime Minister in December 1905, hoping in vain that the Liberal leader Campbell-Bannerman would be unable to form a strong government. These hopes were dashed when Campbell-Bannerman faced down an attempt (the "Relugas Compact") to "kick him upstairs" to the House of Lords. The Conservatives were defeated by the Liberals at the general election the following January (in terms of MPs, a Liberal landslide), with Balfour himself losing his seat at Manchester East. Only 157 Conservatives were returned to the House of Commons, at least two-thirds of them followers of Chamberlain, who briefly chaired the Conservative MPs until Balfour won a safe seat in the City of London.

Arthur Balfour's Government, July 1902-December 1905

- Arthur Balfour - First Lord of the Treasury, Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Commons

- Lord Halsbury - Lord Chancellor

- The Duke of Devonshire - Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords

- Aretas Akers-Douglas - Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Lansdowne - Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Joseph Chamberlain - Secretary of State for the Colonies

- St John Brodrick - Secretary of State for War

- Lord George Hamilton - Secretary of State for India

- Lord Selborne - First Lord of the Admiralty

- Charles Thomson Ritchie - Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Gerald Balfour - President of the Board of Trade

- Sir William Hood Walrond - Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Lord Balfour of Burleigh - Secretary for Scotland

- George Wyndham - Chief Secretary for Ireland

- Walter Hume Long - President of the Local Government Board

- Robert William Hanbury - President of the Board of Agriculture

- Lord Londonderry - President of the Board of Education

- Lord Ashbourne - Lord Chancellor of Ireland

- Lord Windsor - First Commissioner of Public Works

- Austen Chamberlain - Postmaster-General

Changes

- May 1903 - Lord Onslow succeeds R.W. Hanbury at the Board of Agriculture.

- September-October 1903 - Lord Londonderry succeeds the Duke of Devonshire as Lord President, while remaining also President of the Board of Education. Lord Lansdowne succeeds Devonshire as Leader of the House of Lords, remaining also Foreign Secretary. Lord Salisbury succeeds Balfour as Lord Privy Seal. Austen Chamberlain succeeds Ritchie at the Exchequer. Chamberlain's successor as Postmaster-General is not in the Cabinet. Alfred Lyttelton succeeds Joseph Chamberlain as Colonial Secretary. St John Brodrick succeeds Lord George Hamilton as Secretary for India. Hugh Arnold-Forster succeeds Brodrick as Secretary for War. Andrew Graham-Murray succeeds Lord Balfour of Burleigh as Secretary for Scotland.

- March 1905 - Walter Hume Long succeeds George Wyndham as Irish Secretary. Gerald Balfour succeeds Long at the Local Government Board. Lord Salisbury, remaining Lord Privy Seal, succeeds Balfour at the Board of Trade. Lord Cawdor succeeds Lord Selborne at the Admiralty. Ailwyn Fellowes succeeds Lord Onslow at the Board of Agriculture.

Later career

After the disaster of 1906 Balfour remained party leader, his position strengthened by Joseph Chamberlain's removal from active politics after his stroke in July 1906, but he was unable to make much headway against the huge Liberal majority in the House of Commons. An early attempt to score a debating triumph over the government, made in Balfour's usual abstruse, theoretical style, saw Campbell-Bannerman respond with: "Enough of this foolery," to the delight of his supporters in the House. Balfour made the controversial decision, with Lord Lansdowne, to use the heavily Unionist House of Lords as an active check on the political program and legislation of the Liberal party in the House of Commons. Numerous pieces of legislation were vetoed or altered by amendments between 1906 and 1909, leading David Lloyd George to remark that the Lords had become "not the watchdog of the Constitution, but Mr. Balfour's poodle." The issue was eventually forced by the Liberals with Lloyd George's so-called People's Budget, provoking the constitutional crisis that eventually led to the Parliament Act 1911, which replaced the Lords' veto authority with a greatly reduced power to only delay bills for up to two years. After the Unionists had failed to win an electoral mandate at either of the General Elections of 1910 (despite softening the Tariff Reform policy with Balfour's promise of a referendum on food taxes), the Unionist peers split to allow the Parliament Act to pass the House of Lords, in order to prevent a mass-creation of new Liberal peers by the new King, George V. The exhausted Balfour resigned as party leader after the crisis, and was succeeded in late 1911 by Andrew Bonar Law.

Balfour remained an important figure within the party, however, and when the Unionists joined Asquith's coalition government in May 1915, Balfour succeeded Winston Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. When Asquith's government collapsed in December 1916, Balfour, who seemed for a time a potential successor to the premiership, became Foreign Secretary in Lloyd George's new administration, but was not actually included in the small War Cabinet, and was frequently left out of the inner workings of the government. Balfour's service as Foreign Secretary was most notable for the issuance of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, a letter to Lord Rothschild promising the Jews a "national home" in Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire.

Balfour resigned as Foreign Secretary following the Versailles Conference in 1919, but continued in the government (and the Cabinet after normal peacetime political arrangements resumed) as Lord President of the Council. In 1921-22 he represented the British Empire at the Washington Naval Conference.

In 1922 he, along with most of the Conservative leadership, resigned with Lloyd George's government following the Conservative back-bench revolt against the continuance of the coalition. Bonar Law soon became Prime Minister. In 1922 Balfour was created Earl of Balfour. Like many of the Coalition leaders he did not hold office in the Conservative governments of 1922-4, although as an elder statesman he was consulted by the King in the choice of Baldwin as Bonar Law's successor as Conservative leader in May 1923. When asked by a lady whether "dear George" (the much more experienced Lord Curzon) would be chosen he replied, referring to Curzon's wealthy wife Grace, "No, dear George will not but he will still have the means of Grace."

Balfour was again not initially included in Stanley Baldwin's second government in 1924, but in 1925 he once again returned to the Cabinet, serving in place of the late Lord Curzon as Lord President of the Council until the government ended in 1929. In 1925 he visited the Holy Land.[3]

Apart from a number of colds and occasional influenza, Balfour had enjoyed good health until the year 1928, and remained until then a regular tennis player. At the end of that year most of his teeth had to be removed and he began to suffer from the unremitting circulatory trouble which ended his life. Late in January 1929 Balfour was conveyed from Whittingehame to Fisher's Hill, his brother Gerald's home near Woking, Surrey. In the past he had suffered from occasional bouts of phlebitis and by late 1929 he was immobilised by it. Finally, soon after receiving a visit from his friend Chaim Weizmann, Balfour died at Fisher's Hill on 19 March 1930. At his request a public funeral was declined and he was buried on 22 March beside members of his family at Whittingehame in a Church of Scotland service, though he also belonged to the Church of England. Despite the snowy weather, attenders came from far and wide. By special remainder, the title passed to his brother Gerald.

Personality

Balfour was unusual for himself as much as for his politics. He developed a manner well known to his friends, which has been described as the Balfourian manner. Harold Begbie, a journalist of the period wrote a book called Mirrors of Downing Street. In this little known work, he criticised Balfour heavily for his manner, personality and self-obsession. However even when this is taken into account, through that level of criticism one can see a different side to Balfour, a positive shy side to his personality. The sections of the work dealing with Balfour's personality have been reproduced below.

This Balfourian manner, as I understand it, has its roots in an attitude of mind--an attitude of convinced superiority which insists in the first place on complete detachment from the enthusiasms of the human race, and in the second place on keeping the vulgar world at arm's length.It is an attitude of mind which a critic or a cynic might be justified in assuming, for it is the attitude of one who desires rather to observe the world than to shoulder any of its burdens; but it is a posture of exceeding danger to anyone who lacks tenderness or sympathy, whatever his purpose or office may be, for it tends to breed the most dangerous of all intellectual vices, that spirit of self-satisfaction which Dostoievsky declares to be the infallible mark of an inferior mind.

To Mr. Arthur Balfour this studied attitude of aloofness has been fatal, both to his character and to his career. He has said nothing, written nothing, done nothing, which lives in the heart of his countrymen. To look back upon his record is to see a desert, and a desert with no altar and with no monument, without even one tomb at which a friend might weep. One does not say of him, "He nearly succeeded there," or "What a tragedy that he turned from this to take up that"; one does not feel for him at any point in his career as one feels for Mr. George Wyndham or even for Lord Randolph Churchill; from its outset until now that career stretches before our eyes in a flat and uneventful plain of successful but inglorious and ineffective self-seeking.

There is one signal characteristic of the Balfourian manner which is worthy of remark. It is an assumption in general company of a most urbane, nay, even a most cordial spirit. I have heard many people declare at a public reception that he is the most gracious of men, and seen many more retire from shaking his hand with a flush of pride on their faces as though Royalty had stooped to inquire after the measles of their youngest child. Such is ever the effect upon vulgar minds of geniality in superiors: they love to be stooped to from the heights.

But this heartiness of manner is of the moment only, and for everybody; it manifests itself more personally in the circle of his intimates and is irresistible in week-end parties; but it disappears when Mr. Balfour retires into the shell of his private life and there deals with individuals, particularly with dependants. It has no more to do with his spirit than his tail-coat and his white tie. Its remarkable impression comes from its unexpectedness; its effect is the shock of surprise. In public he is ready to shake the whole world by the hand, almost to pat it on the shoulder; but in private he is careful to see that the world does not enter even the remotest of his lodge gates.

"The truth about Arthur Balfour," said George Wyndham, "is this: he knows there's been one ice-age, and he thinks there's going to be another."

Little as the general public may suspect it, the charming, gracious, and cultured Mr. Balfour is the most egotistical of men, and a man who would make almost any sacrifice to remain in office. It costs him nothing to serve under Mr. Lloyd George; it would have cost him almost his life to be out of office during a period so exciting as that of the Great War. He loves office more than anything this world can offer; neither in philosophy nor music, literature nor science, has he ever been able to find rest for his soul. It is profoundly instructive that a man with a real talent for the noblest of those pursuits which make solitude desirable and retirement an opportunity should be so restless and dissatisfied, even in old age, outside the doors of public life.

—Begbie, Harold: Mirrors of Downing Street- some political reflections, Mills and Boon (1920), p. 76–79

Winston Churchill once compared Balfour to Herbert Asquith by stating, "The difference between Balfour and Asquith is that Arthur is wicked and moral, while Asquith is good and immoral."

Writings and academic achievements

Balfour's writings include:

- The Humours of Golf, a chapter of the Badminton Library's volume on Golf (1890)

- Essays and Addresses (1893).

- The Foundations of Belief, being Notes introductory to the Study of Theology (1895).

- Questionings on Criticism and Beauty (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1909), based on his 1909 Romanes Lecture.

- Theism and Humanism (1915), based on his first series of Gifford Lectures given in 1914 and is still in print. In 1962, Oxford writer C. S. Lewis told Christian Century that Theism and Humanism was one of the ten books that most influenced his thought.

- Theism and Thought (1923) based on the second in his Gifford Lectures, which were given in 1922.

He was made Doctor of Laws of the University of Edinburgh in 1881; of the University of St Andrews in 1885; of the University of Cambridge in 1888; of the Universities of Dublin and Glasgow in 1891; Lord Rector of the University of St Andrews in 1886; of the University of Glasgow in 1890; Chancellor of the University of Edinburgh in 1891; member of the Senate of the University of London in 1888; and Doctor of Civil Law of the University of Oxford in 1891. He was president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1904, and became a fellow of the Royal Society in 1888. He was known from early life as a cultured musician, and became an enthusiastic golf player, having been captain of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews in 1894-1895. He was president of the Aristotelian Society from 1914 to 1915.

He was also a member of the Society for Psychical Research, a society dedicated to studying psychic and paranormal phenomena, and its president from 1892-1894.

Popular culture

- Balfour was the subject of several parody novels based on Alice in Wonderland, such as Caroline Lewis's Clara in Blunderland (1902) and Lost in Blunderland (1903).[4],[5]

- The character Arthur Balfour, plays a supporting, if off-screen role in Upstairs, Downstairs, promoting the family patriarch, Richard Bellamy, to the position of Civil Lord of the Admiralty.

See also

- Balfour Declaration of 1917

- Gathering of Israel

- Palm Sunday Case

References

- Torrance, David, The Scottish Secretaries (Birlinn 2006)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tuchman, The Proud Tower, p. 46.

- ↑ Balfour, Arthur in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- ↑ "In the Promised Land". Time Magazine. 13 April 1925. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,720211,00.html.

- ↑ Sigler, Carolyn, ed. 1997. Alternative Alices: Visions and Revisions of Lewis Carroll's "Alice" Books. Lexington, KY, University Press of Kentucky. Pp. 340-347

- ↑ Dickinson, Evelyn. 1902. "Literary Note and Books of the Month", in United Australia, Vol. II, No. 12, 20 June 1902

Further reading

Prime sources:

- Harcourt Williams, Robin (Editor): The Salisbury- Balfour Correspondence: 1869- 1892, Hertfordshire Record Society (1998)

Secondary sources:

Biography:

- Adams, R.J.Q: Balfour: The Last Grandee, John Murray, 2007

- Anderson, Bernard: Arthur James Balfour", Grant Richards, 1903

- Dugdale, Blanche: Arthur James Balfour, First Earl of Balfour KG, OM, FRS- Volume 1, Hutchinson and Co, 1936

- Dugdale, Blanche: Arthur James Balfour, First Earl of Balfour KG, OM, FRS- Volume 2- 1906- 1930, Hutchinson and Co, 1936

- Egremont, Max: A life of Arthur James Balfour, William Collins and Company Ltd, 1980

- Green, E. H. H. Balfour (20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century); Haus, 2006. ISBN 1904950558

- Raymond, E.T: A life of Arthur James Balfour, Little, Brown, 1920

- Young, Kenneth: Arthur James Balfour: The happy life of the Politician, Prime Minister, Statesman and Philosopher- 1848- 1930, G. Bell and Sons, 1963

Other:

- Brendon, Piers: Eminent Edwardians (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1980) ISBN 0-395-29195-X

- Begbie, Harold: Mirrors of Downing Street- some political reflections, Mills and Boon (1920)

- Tuchman, Barbara W: The Proud Tower - A Portrait of the World Before the War (Macmillan, 1966)

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Arthur Balfour

- More about Arthur James Balfour on the Downing Street website.

- Archival material relating to Arthur Balfour listed at the UK National Register of Archives

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Charles Dilke |

President of the Local Government Board 1885 – 1886 |

Succeeded by Joseph Chamberlain |

| Preceded by The Earl of Dalhousie |

Secretary for Scotland 1886 – 1887 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Lothian |

| Preceded by Sir Michael Hicks-Beach |

Chief Secretary for Ireland 1887 – 1891 |

Succeeded by William Lawies Jackson |

| Preceded by W.H. Smith |

First Lord of the Treasury 1891–1892 |

Succeeded by William Ewart Gladstone |

| Leader of the House of Commons 1891–1892 |

||

| Preceded by The Earl of Rosebery |

First Lord of the Treasury 1895–1905 |

Succeeded by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| Preceded by Sir William Vernon Harcourt |

Leader of the House of Commons 1895–1905 |

|

| Preceded by The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury |

Lord Privy Seal 1902–1903 |

Succeeded by The 4th Marquess of Salisbury |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 11 July 1902 – 5 December 1905 |

Succeeded by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

|

| Preceded by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

Leader of the Opposition 1905 – 1911 |

Succeeded by Andrew Bonar Law |

| Preceded by Winston Churchill |

First Lord of the Admiralty 1915 – 1916 |

Succeeded by Sir Edward Carson |

| Preceded by The Viscount Grey of Fallodon |

Foreign Secretary 10 December 1916 – 23 October 1919 |

Succeeded by The Earl Curzon of Kedleston |

| Preceded by The Earl Curzon of Kedleston |

Lord President of the Council 1919 – 1922 |

Succeeded by The 4th Marquess of Salisbury |

| Preceded by The Marquess Curzon of Kedleston |

Lord President of the Council 1925 – 1929 |

Succeeded by The Lord Parmoor |

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

| Preceded by Robert Dimsdale |

Member of Parliament for Hertford 1874 – 1885 |

Succeeded by Abel Smith |

| New constituency | Member of Parliament for Manchester East 1885 – 1906 |

Succeeded by Thomas Gardner Horridge |

| Preceded by Alban Gibbs |

Member of Parliament for the City of London 1906 – 1922 |

Succeeded by Edward Grenfell |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by W.H. Smith |

Conservative Leader in the Commons 1891–1911 |

Succeeded by Andrew Bonar Law |

| Preceded by The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury |

Leader of the British Conservative Party 1902–1911 |

|

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by The Lord Reay |

Rector of the University of St Andrews 1886–1889 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Dufferin and Ava |

| Preceded by The Earl of Lytton |

Rector of the University of Glasgow 1890 – 1893 |

Succeeded by John Eldon Gorst |

| Preceded by Lord Glencorse |

Chancellor of the University of Edinburgh 1891–1930 |

Succeeded by J. M. Barrie |

| Preceded by The Lord Rayleigh |

Chancellor of the University of Cambridge 1919–1930 |

Succeeded by Stanley Baldwin |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Earl of Balfour 1922 – 1930 |

Succeeded by Gerald William Balfour |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by John Ringling |

Cover of Time Magazine 13 April 1925 |

Succeeded by Walter P. Chrysler |

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

.svg.png)